From the February 2009 Idaho Observer:

An interview with Daniel Shays

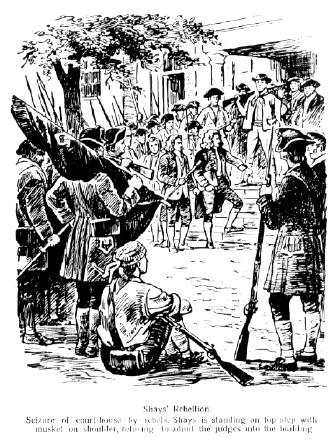

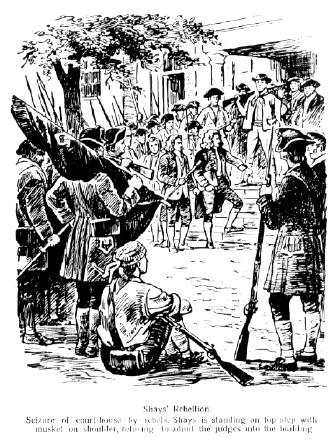

Daniel Shays (1741-1825) of Massachusetts fought in two American revolutions.

In the first one, he was a captain in the 5th Massachusetts Regiment and fought

the British with distinction at Bunker Hill, Ticonderoga, Saratoga and Stony

Point. Shays resigned from the army in 1780 and settled in Pelham, Mass. He

became a farmer and held several positions in local government. By September

of 1787, he was fighting a second revolution—this time against the government

of Massachusetts. With the backing of 800 families and about the same number

of militiamen, Shays decided to prevent the court from signing indictments against

farmers who were behind in taxes that had become as unfair as those levied by

the British king a decade before. Shays, who refused to allow a portrait of

himself so we do not know what he looked like, forever maintained that he fought

both revolutions for the same reason.

By Sean Swain

While it is typical over the holidays for someone to get visited by the ghosts of Christmas past, present and future, just before the holidays I was supernaturally contacted by a ghost, strangely, of America’s revolutionary past. His name was Daniel Shays. I took the occasion of this haunting as an opportunity to interview him. The following is my account of the exchange.

S Swain: Can you tell me a little bit about yourself?

D Shays: Yes, Sir. My name is Daniel Shays and I was a farmer in the Commonwealth o’ Massachusetts; my family and neighbors grew our own food.

SS: Besides farming, was there something of historical significance you did that people might remember?

DS: Well, yes, I reckon folks remember the Shays’ rebellion that began in 1786.

SS: 1786? That would mean that you’re ‘er, quite . . . old.

DS: No, Sir. Actually, I’m dead. But since there’s nobody alive to say what needs to be said, I’ve been pulled out of the grave to say it. And I don’t really mind, but I can’t figure out how I can be much help to you.

SS: Perhaps you could tell us a little bit about Shays’ Rebellion.

DS: Yes, Sir. But, first off, it wasn’t a rebellion, not as I see it, anyhow. A rebellion is where people get disobedient to the rightful authorities. They rebel like unruly children against their parents. And that’s not how it was. We weren’t rebelling, we were revolting. We weren’t unruly children and those dandies in fancy suits and robes weren’t our parents. They were just some money-grubbin’...Excuse my language...

SS: That’s okay.

DS: My fire’s still burning on that sometimes.

SS: Makes sense.

DS: Anyhow, these folks were trying to take our farms from us. I was raised that if you can’t say something nice about a fellow, well, don’t say anything at all. And I can’t think o’ anything nice to say about those fellows taking our farms.

SS: Who were they, and why were they trying to take your farms?

DS: Well, you see, it’s like this: We had just fought the War for Independence. And I know you got some ideas about how all that was, but most of us were simple folks and we didn’t fight for big ideas. We fought because we wanted to be left alone to live our lives and not get bossed around or have somebody reaching in our pockets.

So after the war, everything got bad. Folks were workin’ hard and having a bad time tryin’ to make it from day to day and, even though we didn’t have a king any more, we were still paying taxes to folks who dressed better’n we did and didn’t have dirt under their fingernails. And no matter what you call them, if folks dress nice and don’t have dirt under their nails and they are giving the orders and you are doing the paying, well then you have a king. And all of us were doin’ the sweating and the bleeding and losing our farms to the bankers. So really, the bankers were our kings.

Good people were getting thrown off their land. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen it but I saw some good, proud folks, people with dignity, thrown out of their homes and off their land. I saw mothers with their arms full of crying, hungry children. And that does something to you.

They weren’t bad people. I knew them. They were good people that cared about their neighbors. They’d help you dig a well or bake your family some bread. But those men from the banks were not good people. I don’t know people like that who can just come along and make a mother pick up her kids and go out in the cold with nowhere to go. Or humiliate a man and leave him with his family wonderin’ how they were going to eat. And let the land sit fallow and the house sit empty. It’s not right.

SS: So what did you do?

DS: Well, sir, I have to explain somethin’ before I get to that. It’s like this. You have to understand this before you can understand what we were up against. If a robber comes to your house and he tries to hurt your family and take your horses, well, you shoot him because you know he’s a scoundrel an’ you got to protect yours. You see?

SS: Uh-huh.

DS: And if a wolf comes along and tries to get at your chickens or your cows, you shoot him too. It’s not ‘cause you’re feelin’ mean against him or anything, but he’s taking food out of your family’s mouth, so you treat him like a scoundrel. You see?

SS: I think I do.

DS: But you can’t shoot the bank, sir. You can’t shoot the government. They aren’t a person like a robber or a wolf and you can look and look but you won’t find ‘em. They come along and they take from you and take from your family and they do you harm, but who do you shoot? You can’t shoot the taxman, ‘cause you aim your musket at him and he says he’s just doing his job and it’s not his fault, it’s just how the system works. And you aim your gun at the bill collector and he says it’s not his fault either and he’s just doin’ what he’s told. They’ll tell you they have a wife and children and they get to cryin’ that they’re not bad men. And maybe they’re not. But you aren’t either and you get to feelin’ all stewed up inside ‘cause you can’t shoot them but you want to shoot somebody. Because they’re taking from your family. You see?

SS: Yes.

DS: But those bankers know that. They sit behind their desks and send some other poor fellow. And the government men sit behind their desks and send some other poor stooge, too. They’ve got it all figured out. They say, "These bumpkins won’t know who to shoot if we make it complicated. They’ll get off the land and hand over their money because we’ve papers and the law on our side." It’s not like the robber or the wolf coming to your house. When you’re gettin’ robbed by the banks and the government, the robbers and the wolves are hidin’ behind desks.

That was the situation we were in. I wanted to make sure you knew we weren’t just bad folks trying to raise some hell.

SS: So that’s what led to Shays’ Rebellion?

DS: Yes, Sir. We were simple farmers but we got together and decided we weren’t leaving. We weren’t payin’ any more taxes to a government that wasn’t ours and we weren’t coming off the land.

SS: So, what did the bankers and the government do?

DS: They sent some folks to talk to us. To tell us it was all official and there wasn’t anything we could do, so we ought to go peacefully.

Well, we didn’t see it that way. There was something we could do. We could stay. See, the banks an’ the government men, they thought their pieces of paper are what make things real. And if the piece of paper says it, well that’s how it has to be. But we were of a different mind. We said, "Our boots are still touching this soil and our muskets are as real as that piece o’ paper."

So the government sent lawmen to get us off our land. Sheriffs. Men with muskets.

SS: What happened?

DS: We had guns, too. So we shot ‘em.

SS: But the people who came to evict you were the law!

DS: So? Any law that makes children go hungry isn’t a law. Any law that throws a man off his land is no law. See, we knew we were at war—again.

Nowadays, you have a word, "class warfare," but you only use it when it’s poor folks who’ve had enough. Then it’s a word you use that makes it out like somebody’s stirrin’ up the savages. You don’t ever see it as class warfare when rich folk like bankers and bosses are starvin’ the children of poor working people. You just see it like that’s the way it is.

Well, we saw them waging war against us and against our lives and law isn’t law when it says you’ve got to stop livin’ and bein’; when somebody else has a right to more’n they need and your children don’t have a right to food.

SS: But weren’t you afraid of going to jail?

DS: Jail? Haven’t you been listening?

SS: Well, I –

DS: Jail was not an option. They could kill us or they could leave us be.

So after we shot the lawmen, the bankers went right to the judges and the judges wrote out some other piece o’ paper and ordered us off the land, which just made us angrier. ‘Cause by then you’d o’ thought these smart fellers would o’ known.

SS: Known what?

DS: That we outnumbered them. There were more of us than there were o’ them. What I mean is, we were the people. You can stack up all the bankers and judges and law men there are, but there aren’t many o’ them. And they may have lots of pieces o’ paper to wave at you, but not many of them can shoot straight. Can’t hit the broad side of a barn from the inside.

So when the judges signed the orders for the bankers, we went to the courtroom and it was just as I thought. It’s a lot harder for a man, even a judge, to do a bad thing when he’s got to look you in the eye and do it. So, in the end, those judges were a sight more understandin’ when they had to deal with us face to face.

SS: Maybe it was because you had those muskets.

DS: I reckon so. It’s been my experience that if you shoot a few judges, the rest start acting right.

SS: I can see how that might work, but once you got to that point...

DS: Burnin’ down banks and courthouses an’ shootin’ folks who tried to stop us, you mean?

SS: ...didn’t they call in the federal troops?

DS: Well, we figured they might try and do that, so we said to ourselves, "Why not attack them first?" So that’s what we did.

SS: You attacked the army?

DS: Yes, Sir. We had shot the law, we had shot bankers and we had shot judges, but we didn’t shoot anybody that didn’t have a shootin’ coming to him. At that point, we knew that troops would be arrivin’ to put us in our place. And that meant they’d come to our farms to round us up and we’d be right back at the start o’ things, only the troops would be shootin’ and burnin’ us out and after all that, we’d still lose our farms. We didn’t want the shootin’ an’ burnin’ to happen on our farms, so we had the idea to go to the armory and get her over with. Besides, if we could get their guns, they’d have no way to ever put us down. We’d be giving the orders. So, we attacked the army.

SS: How’d that work out?

DS: Well, we couldn’t burn ‘em out and we couldn’t make ‘em surrender, but I suspect they lost more’n we did. An’ we figured we’d made our point, anyhow. We weren’t scared to fight. If they were looking for more of what we gave ‘em, they knew where to come find it. So we—most of us—went home.

SS: Did they come after you?

DS: No, Sir. After a long winter of rude justice, the bankers, lawmen and judges who didn’t get shot came to a new way of seeing things. We had a new understanding. They wouldn’t come to our farms waving around court orders and demanding taxes and we wouldn’t shoot ‘em.

SS: Sounds fair.

DS: That’s what we thought.

SS: So, do you believe there are any lessons we could draw from your experience and apply them to our situation today?

DS: Well, there’s really no nice way to say this, you know. You folks let the tax men rob you and the bankers rob you and you let the tax men give your money to the bankers who already robbed you and none of them are getting shot.

You let the bankers rob you and you don’t rob them back.

SS: But Mr. Shays, with the technology they have now—it’s very advanced. Not like in your time. You can’t just go robbing a bank.

DS: I didn’t say "banker." I said, "bankers." You don’ rob one, you rob them all. And not just you. Everybody. You take back that $700 billion the tax man stole from you and gave to the bankers. If the people had that much money, they wouldn’t need any bank. Wouldn’t need any government either.

Instead, you get thrown off of your jobs and thrown out of your houses and you just pack up your stuff an’ go. It’s like there’s no fight left in you people. Somebody in fine clothes waves a paper at you folks and says it’s so and you just go along with it. Why, they’d have to shoot me. Yes, Sir. And I’d take a good share o’ them with me.

SS: But you can’t do that any more. Law enforcement has armor and automatic weapons and helicopters and if they don’t kill you, the courts will put you away forever. Maybe send you to Guantanamo Bay. You can’t fight the system any more. It’s too powerful.

DS: Maybe it’s because I don’t talk quite right, but you still don’t understand me. They knew it. They figured it out. But you haven’t figured it out yet.

SS: Figured out what?

DS: You outnumber ‘em.

Sean Swain is a wrongfully-convicted political prisoner being held by the state of Ohio. Mr. Shays could not have "visited" him at a more appropriate time. While the times and circumstances have changed, the temptation for bankers and governments to throw people in prison and steal their property has not. If you would like to thank him for this inspired interview, write Sean Swain #243 205, PO Box 80033, Toledo, Ohio 43608.